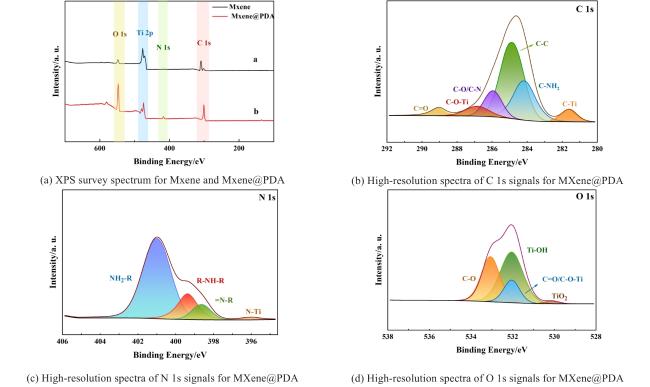

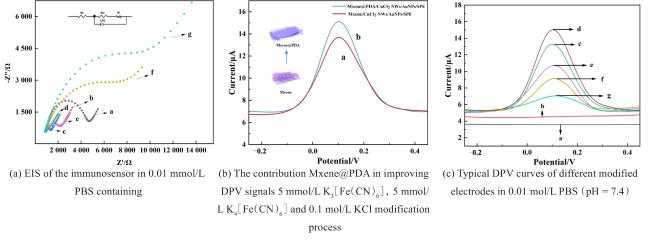

Two-dimensional (2D) materials, such as Mxene, stand out due to their unique metallic conductivity, high specific surface area, and numerous functional groups. These advantageous characteristics have led to the widespread use of Mxene in the fields of energy storage

[12], biotherapeutic

[13, 14], electrocatalytic water splitting

[15], sensors

[16, 17], and more. However, the strong van der Waals force between adjacent sheets make is easy to produce densely packed lamellas, limiting its practical application

[13, 14, 18]. To address this, researchers have explored the use of different nanomaterials as additives for interlayer of Mxene, such as MWNTs and GO. Additionally, dopamine (DA), a small and low-cost organic molecule, can spontaneously polymerize and synthesize polydopamine (PDA) films on various surfaces under weakly alkaline conditions

[19]. Moreover, the high content of Catechol in PDA provides robust adhesive properties, making it particularly advantageous for coating nanomaterials, generating nano coatings and altering their surface properties

[10]. PDAs can also serve as binders and crosslinkers, not only to immobilize inorganic nanoparticles, but also to further functionalize polymers for enhanced adsorption capacity. For instance, Deng et al.

[20] prepared PDA@Mxene as printing ink, leveraging PDA to enhance the waterproof and antioxidant properties of Mxene. Similarly, Lee et al.

[21] employed DA to create an adhesive layer by

in situ polymerization on MXene, resulting in a composite material with a highly organized and tightly layered structure that not only improves the effective shielding against oxygen and moisture, but also significantly improves the stability of Mxene. However, the potential application properties of Mxene@PDA in biosensor construction requires further exploration.