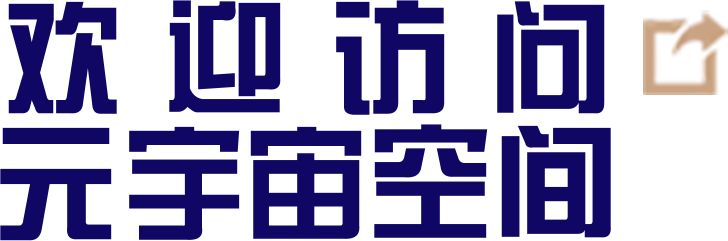

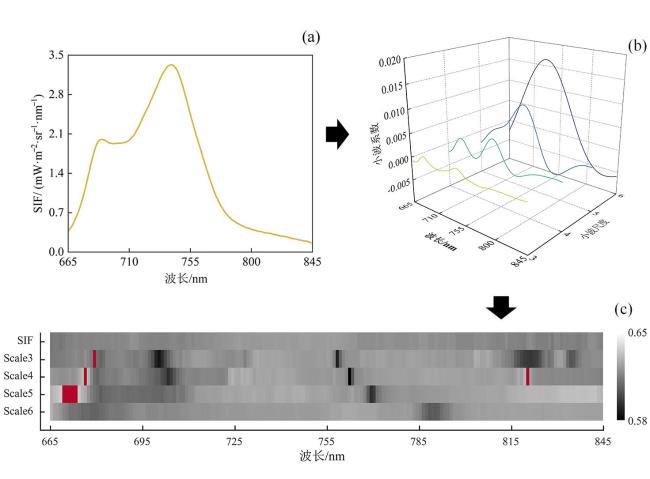

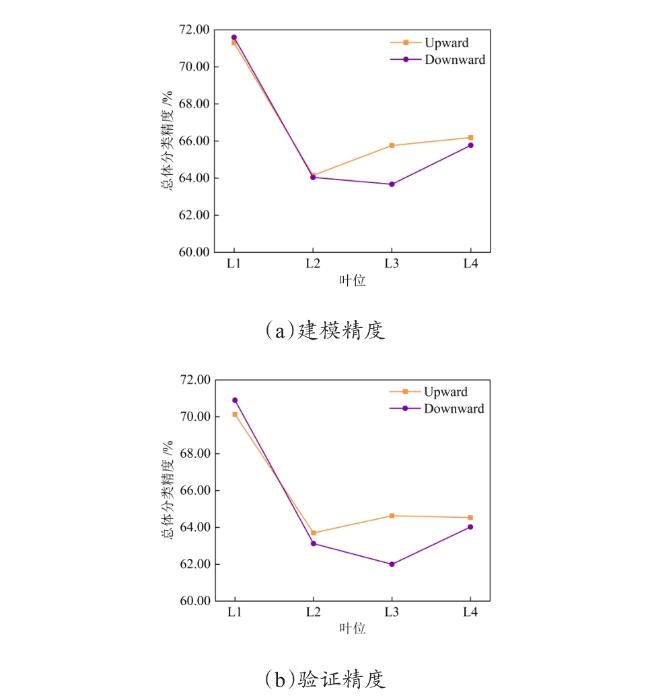

[Objective] Rice blast is considered as the most destructive disease that threatens global rice production and causes severe economic losses worldwide. The detection of rice blast in an early manner plays an important role in resistance breeding and plant protection. At present, most studies on rice blast detection have been devoted to its symptomatic stage, while none of previous studies have used solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) to monitor rice leaf blast (RLB) at early stages. This research was conducted to investigate the early identification of RLB infected leaves based on solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence at different leaf positions. [Methods] Greenhouse experiments and field trials were conducted separately in Nanjing and Nantong in July and August, 2021, in order to record SIF data of the top 1th to 4th leaves of rice plants at jointing and heading stages with an Analytical Spectral Devices (ASD) spectrometer coupled with a FluoWat leaf clip and a halogen lamp. At the same time, the disease severity levels of the measured samples were manually collected according to the GB/T 15790-2009 standard. After the continuous wavelet transform (CWT) of SIF spectra, separability assessment and feature selection were applied to SIF spectra. Wavelet features sensitive to RLB were extracted, and the sensitive features and their identification accuracy of infected leaves for different leaf positions were compared. Finally, RLB identification models were constructed based on linear discriminant analysis (LDA). [Results and Discussion] The results showed that the upward and downward SIF in the far-red region of infected leaves at each leaf position were significantly higher than those of healthy leaves. This may be due to the infection of the fungal pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae, which may have destroyed the chloroplast structure, and ultimately inhibited the primary reaction of photosynthesis. In addition, both the upward and downward SIF in the red region and the far-red region increased with the decrease of leaf position. The sensitive wavelet features varied by leaf position, while most of them were distributed in the steep slope of the SIF spectrum and wavelet scales 3, 4 and 5. The sensitive features of the top 1th leaf were mainly located at 665-680 nm, 755-790 nm and 815-830 nm. For the top 2th leaf, the sensitive features were mainly found at 665-680 nm and 815-830 nm. For the top 3th one, most of the sensitive features lay at 690 nm, 755-790 nm and 815-830 nm, and the sensitive bands around 690 nm were observed. The sensitive features of the top 4th leaf were primarily located at 665-680 nm, 725 nm and 815-830 nm, and the sensitive bands around 725 nm were observed. The wavelet features of the common sensitive region (665-680 nm), not only had physiological significance, but also coincided with the chlorophyll absorption peak that allowed for reasonable spectral interpretation. There were differences in the accuracy of RLB identification models at different leaf positions. Based on the upward and downward SIF, the overall accuracies of the top 1th leaf were separately 70% and 71%, which was higher than other leaf positions. As a result, the top 1th leaf was an ideal indicator leaf to diagnose RLB in the field. The classification accuracy of SIF wavelet features were higher than the original SIF bands. Based on CWT and feature selection, the overall accuracy of the upward and downward optimal features of the top 1th to 4th leaves reached 70.13%、63.70%、64.63%、64.53% and 70.90%、63.12%、62.00%、64.02%, respectively. All of them were higher than the canopy monitoring feature F760, whose overall accuracy was 69.79%, 61.31%, 54.41%, 61.33% and 69.99%, 58.79%, 54.62%, 60.92%, respectively. This may be caused by the differences in physiological states of the top four leaves. In addition to RLB infection, the SIF data of some top 3th and top 4th leaves may also be affected by leaf senescence, while the SIF data of top 1th leaf, the latest unfolding leaf of rice plants was less affected by other physical and chemical parameters. This may explain why the top 1th leaf responded to RLB earlier than other leaves. The results also showed that the common sensitive features of the four leaf positions were also concentrated on the steep slope of the SIF spectrum, with better classification performance around 675 and 815 nm. The classification accuracy of the optimal common features, ↑WF832,3 and ↓WF809,3, reached 69.45%, 62.19%, 60.35%, 63.00% and 69.98%, 62.78%, 60.51%, 61.30% for the top 1th to top 4th leaf positions, respectively. The optimal common features, ↑WF832,3 and ↓WF809,3, were both located in wavelet scale 3 and 800-840nm, which may be related to the destruction of the cell structure in response to Magnaporthe oryzae infection. [Conclusions] In this study, the SIF spectral response to RLB was revealed, and the identification models of the top 1th leaf were found to be most precise among the top four leaves. In addition, the common wavelet features sensitive to RLB, ↑WF832,3 and ↓WF809,3, were extracted with the identification accuracy of 70%. The results proved the potential of CWT and SIF for RLB detection, which can provide important reference and technical support for the early, rapid and non-destructive diagnosis of RLB in the field.